Way back in March at ASAE’s Great Ideas Conference, I had the opportunity to participate in an early morning conversation facilitated by Jeff de Cagna. Rob Barnes (at the time of Fitness Australia and now of Aptify) and Bob Rich (the American Chemical Society), Jeff and I debated the member relationship and, more specifically, why membership associations insist on behaving as if membership is the only relationship people can have with us.

I’ve been rolling this idea around in my head ever since then, and even promised a later blog post. Well, this is it.

Historically, associations have focused heavily, even exclusively, on the membership relationship. Makes sense, right? After all, we’re membership associations.

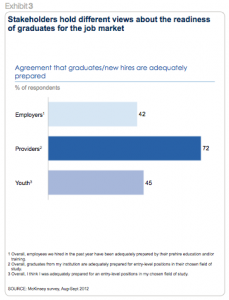

The thing is, we have LOTS of other stakeholders and potential stakeholders, don’t we? Just to name a few: volunteers (committee or ad hoc), subscribers, advertisers, authors, in-person event attendees, virtual event attendees, presenters, speakers, accreditation holders, certification holders, certification students, members of our industry or profession who aren’t association members, beneficiaries of our advocacy work, government officials, legislators (local, state, federal), customers who “just” want to buy products or services from us, our members’ customers, vendors and suppliers who serve our members, and even, in some cases, the general public. And I’m sure there are others.

We have managed to formalize some of these relationships. We offer sponsorships for vendors who want access to our members. We offer non-member rates for publications and events. We track CE credits for our certification holders.

But we also push all these people towards membership. In fact, taking any of the above actions is guaranteed to turn you into a membership lead, who will be pursued relentlessly until she joins or tells us to piss off (or just starts ignoring everything we send her).

Why does everyone have to be a member? Why are we still operating with the “you can have it in any color you want so long as it’s black” mindset? The world has changed to one of mass customization, and we aren’t keeping up with people’s expectations and experiences.

In order to continue to thrive, associations need to figure out ways of formalizing other relationships than the member relationship and allowing space for informal relationships as well. We need to study our audiences far more deeply and extensively, learn about them and what they want, and then become more flexible in our attitudes and offerings in order to meet them where they are, rather than demanding they all fit into the one box we’re willing to provide.